1. Introduction

Brand, regardless of meaning of the name and sign of trademarks, express an emotional relationship between enterprises and customers (Dalvand et al., 2019). According to Ladhari et al. (2017), emotions play a significant role in the purchase process of products and services. Moreover Kurajdová et al. (2015) also argued that consumers obviously play a vital role in the level of success that enterprises achieve, as consumers decide whether to purchase the offered products and services or not and there by determine the prosperity and existenece of and organization. Consumers also tend to share their product experience with their family and friends (Delzen 2014) and according to Richins (1983), bad experiences spread much faster than good experiences. Kanouse (1984) supported this opinion by suggesting that people tend to weigh negative information more heavily than the positive information. However, according to Sternberg (2003), the literature of hate is underdeveloped and that is the reason why the topic of hate is even less studied in the domain and marketing and consumer research. Zarantonello et al. (2016) also stated that treatments of brand hate have selectively focused on narrow emotions whereas hate is a very complex emotion with several primary and secondary emotions.

Basically, the emotional experiences can be divided to two main groups: the positive and the negative so that customers’ emotions towards brands also have positive and negative aspects. When investigating the basic level of emotion categories, Fehr and Rusell (1984) found love and hate was the second most important emotion. Study of Shaver et al. (1987) also confirmed that hate was in the third place out of 213 emotional words. Positive aspects have been frequently discussed and examined in marketing literature as customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, brand romance, brand love, etc., yet the research about negative emotions of brand is scarce (Dalvand et al., 2019).

Studies in psychology approved the fact that negative emotions have greater impacts on behavior than positive ones (Fetcherin, 2019). Besides, consumers do not want to consume is just as important as knowing what they do like (Hogg and Banister, 2001), hence, scholars and companies therefore need to do more and deeper research of dark side phenomenon than only examining the bright side. There have been three different approaches of brand hate such as (i) understanding the emotional expression of brand hate which is grounded in the psychology of the customers (Sternberg 2003), (ii) the customer brand relationship which focuses on the causes of customers’ negative emotions towards brands (Fournier & Alvarez 2013) and (iii) anti – brand behaviors which discusses the consequences of brand hate (Knittel et al., 2016).

From the managerial perspective, brand hate has attracted the concerns of enterprises in the managerial contexts, especially in the era of online society as we are in now. In online environment, news including either good or bad spread faster and to larger geographical space regardless of whether we want it or not. Customers nowadays have stronger power by expressing their thinking, emotions and opinions freely on their own social media account and negative online captions/post mostly attract more attention than the normal or the positve ones. Not only local, small or new brands must cope with the troubles of brand hate, but giant international brands such as Apple, H&M, United airlines, Air asia Nike, and Bata also expreince severe problems due to customers’ brand hate.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Hate

Grounded in psychology literature, brand hate recently has attracted increasing attention from marketing scholars and practitioners with the purpose of understanding the dark side of customers’ emotions and responses. Although the research on customer – brand relationship concept has been engaged by many authors, the negative characteristics seem to have been less studied in favor of positive relationship (Park et al., 2013 and Curina et al., 2020). There are various ways to conceptualize the term – brand hate.

At first, brand hate can be simply defined as negative feelings in contrast with positive feelings – brand love (Khan and Lee 2014). The definition of Khan and Lee (2014) basically considered brand hate same as the brand dislike.

Second, brand hate is a more intense emotional response that the consumers have towards a brand than brand dislike. This approach is supported by the psychologist Sternberg (2003) who suggested that interpersonal hate is not only a more intense form of interpersonal disliking, but also empirically and conceptually it is a distinct construct.

Third, the marketing literature identifies two main components of brand hate as active and passive brand hate (Zarantonello et al., 2016). Moreover, it also contributed to marketing literature Bryson et al. (2013) considered consumer’s dissatisfaction with product performance or negative past experience with brand as a determinant of hate. The possible incongruence between self – image and brand image are ideologically unacceptable due to legal, moral or social corporate wrongdoing. Moreover, marketing author Kucuk (2016) also adopted the previous findings of Sternberg (2003) by following the approach that brand hate has three distinct emotions as disgust, anger and contempt. Disgust refers to the seeking of physical, emotional, or mental distance. Park et al. (2013) stated that when a consumer feels close to a brand, love emotion usually accompanies that feeling and in contrast, when an individual feels averse or distant from a brand, such feelings may be accompanied by disgust. The feeling of contempt is defined by Sternberg (2003) as commitment involving perception of diminution and devaluation. The emotion of anger is expressed by passion under which it is referred to as a kind of anger that leads one to approach the object of hate with a thirst for vengeance, which can also take the form of brand retaliation in its extreme form (Funches et al., 2009) or brand revenge (Johnson et al., 2011).

Fourth, there have been some possible antecedents of brand hate established in the literature such as: negative past experience (experiential avoidance) and symbolic (identity) incongruity, ideological incompatibility (moral avoidance) (Hegner et al., 2017); deficit value avoidance (Lee et al., 2009a), adverting – related avoidance (Knittel et al., 2016).

Fifth, from the perspective of behavioral outcomes, according to Grégoire et al. (2009), and Marticotte et al. (2016), brand hate leads to adversarial actions of avoiding the brand or hateful consumer behaviors ranging from mild to severe retaliation behavior. The public and private complains about brand private and public complaining are classified as the mild outcome behaviors of brand hate whereas the brand retaliation and revenge tend to be more severe. Researches Breivik & Thorbjørnsen (2008), and Kucuk (2019) suggested that the emotion of disgust may lead to the opposite of closeness which is avoidance by switching to another brand. Hence, the switching behavior is also considered as the actionable consequences of brand hate. The most severe outcome behaviors of brand hate could be the willingness to make financial sacrifices to hurt the brand (Jin et al., 2017).

2.2. Deficit Value

According to Lee et al. (2009b), the deficit value or deficit value avoidance occurs when the brands are perceived as representing an unacceptable cost to benefit trade-off. It means the consumer might avoid brands that are perceived as low quality and consequently deficient in value (Lee et al., 2009b). Both practice and literature prove the fact that the perceived quality has strong influence on the customer’s perception towards product/service value, then the purchase intention. Lee et al. (2009b) also considered the unfamiliarity is a dimension of deficit value construct in which the customers might avoid unfamiliar brands because they regard the unfamiliar brands as lower quality and might increase the risk perception. The new brands, therefore, face this challenge from consumers (Knittel et al., 2016). According to Zeithaml (1996), deficit value could be understood as of low quality. Moreover, due to Richardson et al. (1994) the unfamiliarity of brand to consumer is the reason for deficit value avoidance. Other reasons for brand’s deficient perception could be because the products or services offered are inexplicably expensive and lack aesthetic packaging (Lee et al., 2009a). The service quality also has a discriminatory effect on the brand attitude (Song et al., 2020).

H1: Deficit value influences the Brand Hate.

2.3. Negative Past Experience

Negative past experience or experiential avoidance relates to undelivered brand promises stemming from unmet expectations, unpleasant store environment, perceptions of poor brand performance or consumption hassles and inconveniences (Lee et al., 2009a). Negative past experience also resonates from functional inadequacy. Moreover, the inconvenience associated with acquiring the product and negative store environment also are the reasons for negative past experience (Lee et al., 2009b). De Chernatony & Dall’Olmo Riley & (2000) argued that not only the performance, but also the consistency is critical. Whenever the promise of brand is not consistent, it leads to the unstable actual experience of customers although they already have positive experiences with previous buying sections.

H2: Negative past experience influences the Brand Hate.

2.4. Ideology Incompatibility

The ideology incompatibility that so called moral avoidance is defined as the moral conflict between the consumer and the brand (Lee et al., 2009b). One of the dominant aspects of this issue is the anti-hegemony which refers to consumers avoiding the biggest brands in order to prevent the monopolies or because they are associated with corporate irresponsibility (Kozinets & Handelman, 2004). According to Choi and Park (2011), consumers who experience identification with a corporate identity also show positive responses to corporate brand. Ideological incompatibility can also be linked with the country effects (Knittel et al., 2016) and that is termed as country-of-origin avoidance. As discussed in the study of Bloemer et al. (2009), consumes use the country-of-origin as an evaluation scale for product quality assessment. This is the main reason for customer’s boycott behavior with the Chinese origin product which spread across the world in early 2021 or American brands in Islamic countries.

H3: Ideology incompatibility influences the Brand Hate.

2.5. Deceptive Advertising

Deceptive Advertising or misleading advertising has recently been identified as the driving factors of brand hate. Most of marketing research shows that the consumers are strongly influenced by advertising during their whole purchasing process and advertising has direct impact on final customer behavior. According to Knittel (2016), failures of content, celebrity endorsers, music and responses are four components of the deceptive advertising. Content refers to what is being said in the communication process whereas the celebrity endorser is the use of celebrity representing for a brand (Till & Schimp 1998) and the response is an automatic analysis and interpretation mechanism of customers who receive the advertisement message. Knittle et al. (2016) proposed a hypotheis that the failures in advertising lead to customer’s negative emotion to brand.

H4: Deceptive advertising influences the Brand Hate.

2.6. Brand Avoidance

Brand avoidance expresses a negative consumer behaviors such as, consumers turning their back to the specific brand, avoiding the brand, not consuming the brand at all and it can also be entirely switching to a competitor (Hegner et al., 2017). Brand avoidance is also conceptualized as a particular form of anti-consumption and focuses on the deliberate and active rejection of brands (Zarantonello et al., 2016). The rejection of brands represents passive behavior (Berndt et al., 2019) which is more difficult for companies to recognize and counteract. Brand avoidance may be a route to negative brand equity since consumers are prone to react consistently and unfavorably to a particular brand (Odoom et al., 2019).

H5: Brand Hate influences the Brand avoidance.

2.7. Brand Negative Word of Mouth

Brand Negative word-of-mouth is conceptualized by Wetzer et al. (2007) as all negative valence, informal communication between private parties about goods and services and the evaluation thereof whereas East et al. (2007) defined negative word-of-mouth as the extent to which an individual speaks or writes poorly about brand. In the marketing literature, there have been two types of negative word-of-mouth (Christodoulides et al., 2012; Presi et al., 2014) such as private complaining and public complaining. Private complaining is negative talks about brands among friends or group of family members while according to Zeithaml et al. (1996) the public complaining often occurs on social media as on blog posts, websites and social networks. In almost all the studies the private complaining and public complaining are two dimension of brand complaints construct. Dam (2020) stated that brand love had a positive impact on brand commitment and brand positive word of mouth and Zarantonello et al. (2016) stated that negative word-of-mouth is one of the absolute consequences of brand hate.

H6: Brand Hate influences the negative word of mouth.

2.8. Brand Retaliation

Among three actionable consequences of brand hate, the brand retaliation has been classified as an active and direct actions towards the brand (Grégoire et al., 2009). It can be simultaneous or complemented by negative word of mouth and the spread of these complaints online (Abney et al., 2017). According to Hegner et al. (2017), brand retaliation includes many types of actions and attitudes that seek to cause damage or hurt a brand as willingness to make financial sacrifices to hurt the brand (Kucuk 2019). In addition to protesting and complaining about the brands as in the study of Zarantonello et al. (2016), brand hate can also result in direct customers’ punishment behaviors towards the brand (Funches et al. 2009).

H7: Brand Hate influences the brand retaliation.

3. Research Methodology

In order to understand reasons and actionable outcomes of brand hate among Vietnamese netizens, this study designed an online survey and collected responses from internet users during 5 months from the beginning of September 2020 to the end January 2021. A pre-test questionnaire was delivered to marketing professionals and experienced internet users with sample size of 30. The constructs were initially designed in English based on previous constructs of other authors, then translated into Vietnamese for easier surveying. The actual survey was completely developed after correcting and adjusting the pre-test questionnaire.

The online questionnaire was distributed to 500 internet users via emails and Facebook messenger and 358 completed responses were collected which was 71.6% of the total questionnaire sent for the survey. This study employed Smart PLS to conduct descriptive statistics and inferential statistical techniques. Table 1 provides the demographical profile of the respondents. There is mostly a double proportion of Female (68.44%) respondents compared with 31.56% of Male took part in the survey. The two majority groups of respondents have age range from under 23 with 44.97% and from 23 to 35 with 37.99% respectively. The results also indicated that 59.22% of total respondents have family while 40.78% are still single. Officer and student are two biggest groups with 40.50% and 37.99% respectively. This proportion matches with the data value of Age range variable. Facebook is the social network that has the biggest fan club with 69.27% respondents selecting Facebook as the most frequently used social network, while Instagram also occupied 20.67% frequent users.

Table 1: Demographical Profile of the Respondents (n = 358)

Previous studies used various Likert multi-item scales as 7-point Likert scale and 5-point Likert scale, however in this study, we employed 5-point Liker scale with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The current study consists of eight multi-dimensional constructs and five controlled variables. The measurements for these constructs were adopted from other published studies with some minor modifications to fit with the research context.

To measure the mediating variable – brand hate, we combined items from the scales of Hegner et al., (2017), Zeki and Romaya (2008) which is an updated version of Sternberg (2003). The construct deficit value, the negative past experience, the ideological incompatibility was adopted, justified and developed from scales of Romani et al. (2012), Thomson et al., (2012) and Hegner et al., (2017). The brand negative word of mouth and brand avoidance scales have been from Hegner et al., (2017) and Günaydin and Yıldız (2021) while the brand retaliation was adapted from the construct of Leventhal et al., (2014). (Appendix 1).

4. Research Results

This study employed SmartPLS 3.3.3 and applied partial least square structural equation model (PLS-SEM) for the development of theoretical model and the interpretation among the variables. Two main steps for PLS-SEM analysis suggected: (i) evaluation of the measurement models and (ii) the structural model (Hair et al., 2019).

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Models

First, according to Hair et al. (2017), the measurement model was tested for convergent validity through factor loadings, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Both outer loadings and composite reliability (CR) should exceed 0.70 and AVE should be higher than the recommended value of 0.50. From the analysis, it was found that the deficit value, brand hate, brand complaint and brand avoidance constructs would be more reliable and valid after deleting five items: DV2, BH2, BH5, BC6 and BR1 which have the loading values of less than 0.70. All of the rest 38 items satisfied the levels of convergent validity and reliability with outer loadings > 0.70 and AVE > 0.50 (Table 2).

Table 2: Internal Consistency Reliability and Convergent Validity

Note: All item loadings are significant at 0.001 (p < 0.001). CA: Cronbach’s Anpha, AVE: Average variance extracted, CR: composite reliability.

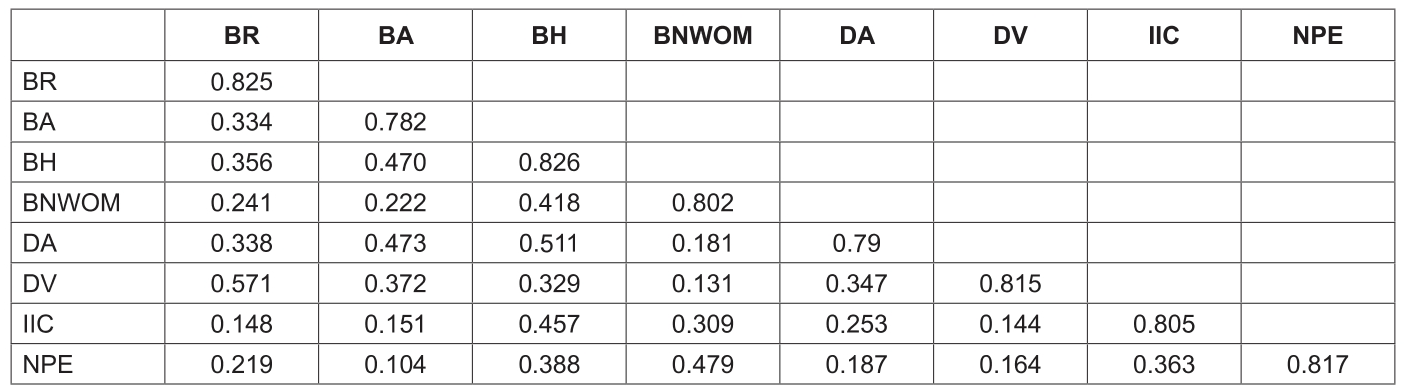

The second step is assessing the extent to which a construct is truly distinct from other constructs by checking the discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2017). According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), the square root of AVE of each construct is larger than its corresponding correlation coefficients, pointing towards adequate discriminant validity. The result of Table 3 indicated that the square roots of the AVE of each variable is greater than any of the correlations involving the said variable, thus, we may conclude that the measurement model showed adequate convergent validity and discriminant validity (Table 3).

Table 3: Discriminant Validity

4.2. Assessment of Structural Models

4.2. Assessment of Structural Models

To assess the structural models, Hair et al. (2017) suggested the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) to check collinearity issues among each set of predictor variables. A VIF value greater than 5 indicate the multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2014), but the analysis results show that the lowest VIF value is 1.562 and the highest value is 2.583 lower than 5 that indicate no multicollinearity issue. Hair et al. (2016) suggested using the SRMR value to access the quality of structural model, the SRMR value should be below 0.10. The result of model fit summary shows the SRMR value of 0.064 – less than the 0.10 - indicating the good fit of model for theory testing (Table 4).

Table 4: R2, q2, SMRM

R2 is the primary way to measure the predictive accuracy of the model and represent the percentage of variance in the dependent variables as explained by the independent variables in the model. As can be seen in Table 4 and compare with Cohen (2013), the R2 values of BH = 0.429, BA = 0.221, BNWOM = 0.174 reached the substantial level and BR = 0.127 reached the moderate level. The Deficit value, Deceptive advertising, Ideology incompatibility and Negative past experience can be explained with around 42.9% of variance can be explained of the Brand Hate, whereas 22.1% of variance can be explained by Brand avoidance, 17.4% of variance of Brand can be explained by Negative Word of Mouth and 12.7% variance can be explained by Brand Retaliation.

According to Gronemus et al. (2010), the path coefficients (β values) indicate the degree of change in the dependent variable for each independent variable. Table 5 shows the path coefficients for all relationships were statistically significant due to all p values < 0.05, therefore H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7 are supported. Hair et al. (2017) also suggested the effect size (f2) and predictive relevance (q2) for each path can be considered. Cohen (2013) gives the guidelines to assess the f2 whereby 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 indicate small, medium and large effects, respectively whereas Akter et.al. (2011) suggested the q2 value larger than 0 indicates that model has predictive relevance for a certain dependent construct.

Table 5: Hypotheses Testing

The results of Table 5 show the medium to large impact of Brand hate on Brand avoidance as f2 values of 0.283; Brand hate on Brand Negative word of mouth as f2 values of 0.211 and Deceptive advertising on Brand hate as f2 values of 0.188 which range from 0.15 to 0.35. All of the rest show the small to medium effect due to the f2 values range from 0.02 to 0.15. The results of Table 5 and Figure 1 also show that all q2 values of 0.285, 0.126, 0.107 and 0.083 exceeded 0 indicating that the brand hate, brand avoidance, brand negative word of mouth and brand retaliation demonstrating acceptable predictive relevance.

Figure 1: Modelling Results

5. Discussion and Conclusion

We conducted this research by highlighting the causes and effects of brand hate from both academic and practical perspective. Grounded in psychology of emotions, recently, brand hate has been examined deeper in marketing and consumer behavior literature. The main aims of this study were exploring and identifying the driven factors and actionable responses of netizens in Vietnam. Through a series of quantitative analysis, we found that brand hate itself consists of two core components as: active brand hate which represent as the emotions of disgust, anger and contempt and passive brand hate which is a combination of disappointment and shame emotions. Brand hate has been influenced by four main factors: deficit value, deceptive advertising, and negative past experience and ideology incompatibility. Findings also provided the evidence to prove that brand hate is the main cause of three actionable behavior of consumers such as brand avoidance, brand negative word of mouth and brand retaliation. Our analysis and supports previous findings of Grégoire et al. (2009), Delzen (2014), Zarantonello et al. (2016), Knittel et al. (2016), Hegner et al. (2017), Fetscherin (2019), Pinto & Brandão (2020). Brand hate in this study plays the mediating role in the relation between the emotional perception and actionable outcomes.

Theoretically, this study already examined and proved the relationships between two new phenomena – deficit value and deceptive advertising and brand hate. Moreover, brand hate also relates to three different levels of customers’ negative actions from mild to severe. Practically, in order to avoid brand hate or customers’ negative emotions, enterprises should ensure that customers will get the exact value or at least equal to what they pay. It means, the price of products must be balanced between offerings and the amount of money and emotional efforts which customers must spend. The customer experience must be put in serious consideration due to its strong influence of brand emotion. The negative experience could be the main cause of both private and public negative word of mouth. Although advertising in most of cases brings expansion opportunities for brands, but the deceptive advertising will lead to brand hate. The use of celebrity, the preparation of advertising message content and of course time to response of company to customer’s voice should be carefully checked to stop the emergence of negative emotions in customers’ mind. In the normal cases, customers may wait to receive the reaction and answer from enterprise but in online environment the expectation of customer is “real time” instead of being put in the waiting list. The late responses are reflected as not respecting behaviors and of course the negative emotions will definitely appear.

Among three identified actionable outcomes, brand avoidance is the mildest one, yet its effects are not mild. According to the items mentioned in brand avoidance scale, customers will buy less or even stop buying and rejecting the brand from their shopping bag. These intentional behaviors will directly relate to the revenue loss and customer loss. In addition, that is the case customer switch to brand’s competitor and this can result in even bigger losses because the competitors have the chance to get bigger market share and revenue. When customer complaints and talks privately with friends, family members of small group of people, the damage to brand is not too high, but when they spread their voice on social networks such as on Facebook posts, close/public groups online, the problems may be out of control. Joining anti-brand groups, to leave anti comments on the social media and boycott behaviors have emerged as the way customer show their responsibility to the online community. Under the psychological effect of negative word of mouth, retaliation is the most severe damage to brand. It may destroy the brand image, brand reputation and even put the brand to an end of life, hence, each enterprise must setup an online communication department which only focus on controlling and directing the communication flows of netizen rather than solving the issues when they have already taken place.

References

- Abney, A. K., Pelletier, M. J., Ford, T. R. S., & Horky, A. B. (2017). # IHateYourBrand: Adaptive service recovery strategies on Twitter. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(3), 281-294. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2016-0079

- Akter, S., D'ambra, J., & Ray, P. (2011). An evaluation of PLS based complex models: The roles of power analysis, predictive relevance and GoF index 2011. Working Papers. University of Wollongong. https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4186&context=commpapers

- Berndt, A., Petzer, D. J., & Mostert, P. (2019). Brand avoidance-a services perspective. European Business Review, 31(2). 179-196. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-02-2017-0033

- Breivik, E., & Thorbjornsen, H. (2008). Consumer brand relationships: an investigation of two alternative models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 443-472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0115-z

- Bryson, D., Atwal, G., & Hulten, P. (2013). Towards the conceptualisation of the antecedents of extreme negative affect towards luxury brands. Qualitative Market Research, 16(4), 393-405. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2013-0043

- Choi, N. H., & Park, D. S. (2011). Individual brand loyalty and the self-corporate connection induced by corporate associations. The Journal of Distribution Science, 9(1), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.15722/jds.9.1.201103.5

- Christodoulides, G., Jevons, C., & Bonhomme, J. (2012). Memo to marketers: Quantitative evidence for change: How user-generated content really affects brands. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(1), 53-64. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-52-1-053-064

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

- Curina, I., Francioni, B., Hegner, S. M., & Cioppi, M. (2020). Brand hate and non-repurchase intention: A service context perspective in a cross-channel setting. Journal of Retailing and consumer services, 54, 102031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.102031

- Dalvand, M. R., Mirabi, V. R., Ranjbar, M. H., & Mohebi, S. (2019). Modelling and Ranking the Antecedents of Brand Hate among Customers of Home Appliance. Journal of System Management, 5(1), 19-40.

- Dam, T. C. (2020). The Effect of Brand Image, Brand Love on Brand Commitment and Positive Word-of-Mouth. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 7(11), 449-457. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no11.449

- De Chernatony, L., & Dall'Olmo Riley, F. (1998). Defining a "brand": Beyond the literature with experts' interpretations. Journal of Marketing Management, 14(5), 417-443. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725798784867798

- Delzen, M. V. (2014). Identifying the motives and behaviors of brand hate (Master's thesis, University of Twente). http://purl.utwente.nl/essays/64731

- East, R., Hammond, K., & Wright, M. (2007). The relative incidence of positive and negative word of mouth: A multi-category study. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(2), 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.12.004

- Fehr, B., & Russell, J. A. (1984). Concept of emotion viewed from a prototype perspective. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(3), 464. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0096-3445.113.3.464

- Fetscherin, M. (2019). The five types of brand hate: How they affect consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 101, 116-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.017

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382-388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Funches, V., Markley, M., & Davis, L. (2009). Reprisal, retribution and requital: Investigating customer retaliation. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 231-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.030

- Gregoire, Y., Tripp, T. M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.1509%2Fjmkg.73.6.18 https://doi.org/10.1509%2Fjmkg.73.6.18

- Gronemus, J. Q., Hair, P. S., Crawford, K. B., Nyalwidhe, J. O., Cunnion, K. M., & Krishna, N. K. (2010). Potent inhibition of the classical pathway of complement by a novel C1q-binding peptide derived from the human astrovirus coat protein. Molecular Immunology, 48(1-3), 305-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molimm.2010.07.012

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Matthews, L. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2016). Identifying and treating unobserved heterogeneity with FIMIX-PLS: part I-method. European Business Review, 28(1), 63-76. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2015-0094

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hegner, S. M., Fetscherin, M., & Van Delzen, M. (2017). Determinants and outcomes of brand hate. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26(1), 13-25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2016-1070

- Hogg, M. K., & Banister, E. N. (2001). Dislikes, distastes and the undesired self: Conceptualizing and exploring the role of the undesired end state in consumer experience. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(1-2), 73-104. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257012571447

- Jin, W., Xiang, Y., & Lei, M. (2017). The deeper the love, the deeper the hate. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01940

- Johnson, A. R., Matear, M., & Thomson, M. (2011). A coal in the heart: Self-relevance as a post-exit predictor of consumer anti-brand actions. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(1), 108-125. https://doi.org/10.1086/657924

- Kanouse, D. E. (1984). Explaining negativity biases in evaluation and choice behavior: Theory and research. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 703-708.

- Khan, M. A., & Lee, M. S. (2014). Prepurchase determinants of brand avoidance: The moderating role of country-of-origin familiarity. Journal of Global Marketing, 27(5), 329-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2014.932879

- Knittel, Z., Beurer, K., & Berndt, A. (2016). Brand avoidance among Generation Y consumers. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 19(1), 27-43. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-03-2015-0019

- Kozinets, R. V., & Handelman, J. M. (2004). Adversaries of consumption: Consumer movements, activism, and ideology. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(3), 691-704. https://doi.org/10.1086/425104

- Bloemer, J., Brijs, K., & Kasper, H. (2009). The CoO-ELM model: A theoretical framework for the cognitive processes underlying country of origin-effects. European Journal of Marketing, 43(1/2), 62-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560910923247

- Kucuk, S. U. (2016). Legality of Brand Hate. In Brand Hate (pp. 93-124). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Kucuk, S. U. (2019). Consumer brand hate: Steam rolling whatever I see. Psychology & Marketing, 36(5), 431-443. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21175

- Kurajdova, K., Taborecka-Petrovicova, J., & Kascakova, A. (2015). Factors influencing milk consumption and purchase behavior-evidence from Slovakia. Procedia Economics and Finance, 34, 573-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01670-6

- Ladhari, R., Souiden, N., & Dufour, B. (2017). The role of emotions in utilitarian service settings: The effects of emotional satisfaction on product perception and behavioral intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.09.005

- Lee, M. S. W., Conroy, D., & Motion, J. (2009a). Brand avoidance: a negative promises framework. Advances in Consumer Research, 36, 421-429.

- Lee, M. S.W., Motion, J., & Conroy, D. (2009b). Anti-consumption and brand avoidance. Journal of Business Research, 62(2), 169-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.024

- Leventhal, R. C., Hollebeek, L. D., & Chen, T. (2014). Exploring positively-versus negatively-valenced brand engagement: a conceptual model. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 23(1), 62-74. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2013-0332

- Marticotte, F., Arcand, M., & Baudry, D. (2016). The impact of brand evangelism on oppositional referrals towards a rival brand. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(6), 538-549. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0920

- Odoom, R., Kosiba, J. P., Djamgbah, C. T., & Narh, L. (2019). Brand avoidance: underlying protocols and a practical scale. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(5), 586-597. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-03-2018-1777

- Park, C. W., Eisingerich, A. B., & Park, J. W. (2013). Attachment-aversion (AA) model of customer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.01.002

- Pinto, O., & Brandao, A. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of brand hate: Empirical evidence from the telecommunication industry. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 30(1), 18-35. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-04-2020-0084

- Presi, C., Saridakis, C., & Hartmans, S. (2014). User-generated content behaviour of the dissatisfied service customer. European Journal of Marketing, 48(9/10), 1600-1625. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2012-0400

- Richardson, P. S., Dick, A. S., & Jain, A. K. (1994). Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 28-36. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224299405800403 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224299405800403

- Richins, M. L. (1983). Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: A pilot study. Journal of Marketing, 47(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224298304700107 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224298304700107

- Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Dalli, D. (2012). Emotions that drive consumers away from brands: Measuring negative emotions toward brands and their behavioral effects. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 55-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2011.07.001

- Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O'connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1061-1086. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061

- Song, B. W., Kim, J. H., & Kim, M. K. (2020). The Effect of Private Brands' Service Quality on Brand Attitude. The Journal of Distribution Science, 18(7), 19-25. https://doi.org/10.15722/jds.18.7.202007.19

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). A duplex theory of hate: Development and application to terrorism, massacres, and genocide. Review of General Psychology, 7(3), 299-328. https://doi.org/10.1037%2F1089-2680.7.3.299 https://doi.org/10.1037%2F1089-2680.7.3.299

- Thomson, M., Whelan, J., & Johnson, A. R. (2012). Why brands should fear fearful consumers: How attachment style predicts retaliation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 289-298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.04.006

- Wetzer, I. M., Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). "Never eat in that restaurant, I did!": Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychology & Marketing, 24(8), 661-680. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20178

- Zarantonello, L., Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2016). Brand hate. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(1), 11-25. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2015-0799

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224299606000203 https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002224299606000203

- Zeki, S., & Romaya, J. P. (2008). Neural correlates of hate. PloS One, 3(10), e3556. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003556

Cited by

- Sense of online betrayal, brand hate, and outrage customers’ anti-brand activism vol.17, pp.4, 2021, https://doi.org/10.21511/im.17(4).2021.07